Kennis /

Valentina Nisi over mobile storytelling

Valentina Nisi Locating Stories

— Interview met Valentina Nisi over het inzetten van mobiele technology om verhalen te vertellen en mensen en plekken te verbinden.

>Valentina Nisi, who led the recent Virtual Platform Stories of Place workshop, uses mobile technologies to chart the tales that link places and people. Her projects have included Weirdview, a series of video reconstructions of the memories of a small Irish community; HopStory, in which a historic building reveals its own tale in navigational sequence as visitors move through it; and The Liberties, an anecdotal tour of the Liberties area in Dublin, complete with a PDA ‘key’ to unlock the stories otherwise invisibly embedded in the places. She talked to Jane Szita.

People and Places

Community stories clearly belong to the people who tell them; so how do you go about editing them?

It depends on the project. With Weirdview, the stories concerned a small community and the material was still in living memory; we therefore let the people themselves decide whether or not they wanted us to use the stories they’d given us in their finished form. With The Liberties, the material was more historical and involved a book adaptation. It was therefore very authored, but here the idea was to use the material as a catalyst to stimulate feedback and memories, which worked very well. Every local who did the Liberties tour with me responded with their own story. People naturally want to exchange stories and add things, there’s an instinct to create a bigger and fuller picture.

Sometimes though, a story is a bit delicate, and intuitively you feel that you should not use it — for example, in one project there was a story involving a death that we dropped. It didn’t seem to fit the tone, and there were relatives still living.

Did the Liberties project encourage outsiders to interact with the community in ‘real life’, aside from listening to the stories?

In some cases, yes. Our feedback from tourists and non-residents showed that they were glad to have had a reason to visit the Liberties to do the tour — otherwise they wouldn’t have gone there, since the area doesn’t have a very salubrious reputation. But whether they interacted with the community as a result of being there depended very much on the type of people they were.

All your projects up to now have been in Ireland, which has a strong storytelling culture.

Yes, any starting point in Ireland generates a story, because they have this rich folkloric tradition and Celtic bardic heritage. They have a huge repertoire of stories, often with a dark humour to them. The Irish have many tales of the supernatural, like the stories about silkies, or seal women. Sometimes they live among people, marry and have children, but they always feel the pull of the sea. I’m currently writing a filmscript on this theme at the Binger Institute in Amsterdam, because I want to study narrative by writing one. Another possible project I’d like to do involves relating this story to the landscape, making the story available on the shores of Donegal, or another suitable setting. I think this area has huge potential for heritage organisations — preserving folklore and making it available using mobile technologies.

Not all cultures have the same facility with storytelling as the Irish perhaps, but then there are other traditions like music which fulfil the same function as a kind of social glue. Now I’m based in Amsterdam, I’m looking at the singing tradition in the Jordaan area, where people just get up in bars and share songs with each other. The songs, like the storytelling, are a form of bonding. The plan is to record the songs and put them on the internet — it’s a type of street singing, and the internet is a new street, after all. There are something like 15 to 20 cafés that are part of this tradition, so perhaps we’ll ask people to dedicate a song to a spot, or perhaps we’ll devise a route so you can experience the songs on an iPod in their original location.

The Jordaan, like the Liberties, was once a Huguenot immigrant area in the 17th century. In poor areas, immigrant areas and historically deprived places, the bonding tradition is particularly strong, whether that’s achieved through music, stories or another art. When people are poor, what do they have to offer each other? Warmth, connection and communication. It’s a coping mechanism, coming together to feel stronger.

Technology and Topography

Given the visual approach of your work, what ways have you found to compensate for the small screen in mobile technologies?

A big part of my research has looked at how to tell stories using a small screen, and obviously some things just don’t work: you can’t use big panoramas, for example. However, the advantage of small-screen media is that it creates a feeling of intimacy (it’s just you and the device), so it’s ideal for close, face-to-face dialogue. It can make you feel special, as though there’s someone there talking just to you. So this is the effect we should set out to exploit with mobile technologies.

Another big factor is attention deficit. Not only is the screen small, but, in real space, especially in an outside environment where all our senses are already occupied, our attention is very divided. So in making stories for mobile technologies we have to consider this and make stories that are simple to follow, because people can’t give all their attention to them.

Why, in this virtual age, should people consider site-specific projects like yours?

First of all, because we can - locational technologies are now blooming, and they offer a lot of potential. Virtual experiences can be good — there are some great examples, like tours of Greek temples online- but they have their limits once you get beyond simple education and information. After all, we don’t experience reality just through our eyes, but through all our senses, including smell and touch. This full range of senses is what gives life its quality of aliveness. When we draw on these senses to create a locational story, the result is a much more immersive experience. In contrast, I tend to find virtual tours a bit sterile. That’s OK from the point of view of education, but I want to create — and I think people like to have - richer experiences, using media and art as a startpoint. My work is trying to capture the essence of communities — and that wouldn’t exist without the physical place.

How can mobile storytelling projects guarantee success?

The interface is a major factor in the success or failure of a project. Interfaces have to be intuitive; if they’re not, they’re obstacles. I’ve good and bad experiences of this — one terrible experience resulted from an inadequate interface, where the status of the stories on the map (which were played, not played and so on) wasn’t clear; the design was cluttered and not easy or pleasant to use. Obviously, design factors are hugely important.

On the other hand, on the Liberties project, I worked with human computer interaction (HCI) expert Ian Oakley. He designed an interface that is so simple to use, people could just work it out without thinking about it, so they could then focus on the experience. It was a big reason for the success of the project, because many of our target group were not very technical. Simpler solutions, of course, take more work.

Why use PDAs rather than mobiles for the Liberties project?

That’s what everyone said! But though it’s true that most people have a mobile, the screen of a PDA is that bit bigger — so it offers more visual potential. And an unexpected benefit was that, because the PDA isn’t as ubiquitous as the mobile, it allowed the experience to seem somehow ‘special’ to the participants.

Do you recommend any particular strategies for the PDA?

The interface you use has to be very condensed and economical - and it must use or reuse conventions people are used to as much as possible — a tap on the screen is clicking; a tick icon means something is completed, and so on. People shouldn’t have to think about the interface, then their experience can just be about the story and the place. The big advantage of the PDA is that you can use video — I’d hesitate to use video on mobile phones, I think stills would work better given the current screen quality.

How about emerging mobile technologies?

The technologies are improving all the time, but I’m quite interested in the potential of things like tags, which were engineered to track store merchandise. These could be used in creative projects. Then you have something like Bluetooth, which didn’t take off but has (I think) fascinating possibilities, because with it you can move in and out of ad hoc networks in an almost viral way.

What did you learn from the Virtual Platform workshop?

Mainly, it showed me how much people are thinking about mobile content now. Five years ago, it was a weird idea; now it’s mainstream. I’m glad I can share what I’ve learned over last few years. The workshop produced some very strong ideas that I’m looking forward to seeing developed. The ideas are the most important thing — people sometimes forget that technology is just a tool, and — especially if they are not very technical - they want to know about the available technology before they have a concept. But in general, the field is much more culture-led than technology-led right now, and that’s a good thing.

Also, I was really amazed at the diversity of the participants — everyone from a performer to educators, and people from not just new media labs but also museums and community organisations. It underlines the fact that what this field needs is people from many different disciplines working together, from research to content generation, from software development to testing and evalution. Mobile storytelling needs interdisciplinary teams, with members who can talk to each other.

From Community to Heritage

What was the initial motivation for your work in mobile storytelling?

When I was writing my thesis in Barcelona, on the work of media artist Antonio Muntadas, I became interested in the idea of empowering communities through storytelling. A lot of inspiration came from the geography of Barcelona itself — both the old Gothic quarter, which got me thinking about all the hidden stories, the things that the tourists don’t see, and also the area across from the Ramblas, where I lived. Whole streets were being torn down in my neighbourhood, and posters were appearing, asking: "Where have your neighbours gone?" The new Ramblas is of course very interesting architecturally, but it’s cold — the fabric of social life is missing. Ultimately, it’s people, the social fabric, that make a place unique, and these people express their shared reality through stories. So I had the idea of filming all the stories of the people who had once lived in the Ramblas, and projecting them onto the new buildings — which, incidentally, is a project I haven’t done yet, though I’d still like to. But it was a starting point for thinking about location and people, and the stories that connect them. Then I did my first story project, Weirdview, as part of my Master’s degree in Dublin, looking at the memories of a small community called Weirview.

How has your original idea of recording ‘the fabric of social life’ developed?

From Weirdview, which was a collection of screen-based stories, I moved on to HopStory, where the story is actually embedded in the building, and experienced as people move around it; so this is playing with narrative, or creating a narrative through physical navigation. Then with The Liberties, which was completed and evaluated last year, the stories are distributed throughout a historic district in Dublin, so this project is very much exploring the ways in which tourism and heritage can be supported by mobile storytelling content. Now I’m talking to people doing projects in museums, education, entertainment, and a digital tour guide for Ghent. The applications are quite wide, especially in the heritage area.

What can mobile storytelling offer to heritage organisations?

I think a more immediate and compelling experience for visitors. Tour guides and museum content already exist of course, but they tend to be very information based. The information is meant to contextualize the objects or sites, but often what happens is that there’s too much information about what I call ‘dead’ aspects of the object, general or very specialised information that doesn’t really link to the life of an object in a personal way. So, for example, you might be looking at a milk jug from 1600 in a museum, and there might be lots of information on the glaze, the pattern, and so on, but this is probably pretty boring unless you’re an expert in ceramics. It’s the great dilemma of the modern age. We have more information than we know how to use, but the big question is how to filter it, so that people can connect to it in a meaningful way. Stories can be an alternative way of communicating information, in a personalised fashion.

Do you mean ‘personalised’ in terms of the object, or the people looking at the object?

Of course, museums can collect users’ characteristics and tailor the information to different people’s preferences, rather on the Gmail model, and I’ve no doubt that we will move towards that. But I mean in terms of the ‘personal’ grassroots history of the object. In terms of our milk jug, I’d like to hear stories about the process of making it — where the clay was found, how it was transported, how it was modelled, how it was sold.

Is it an issue whether a story is fiction, or fact?

I think that stories are inevitably crafted and shaped to fit people’s personalities. People very much transform the facts when they tell stories. But usually, we don’t know if a story is literally true or not. For example, one story from the Liberties project told of a family that had so many babies, that they put them to bed in a chest of drawers. We have no way of checking if this is true or not, but it doesn’t really matter. As a story, it brings the place to life. It tells us a lot about the reality of the time, whether it’s fact or fiction, and it gives an atmosphere that plain facts don’t have.

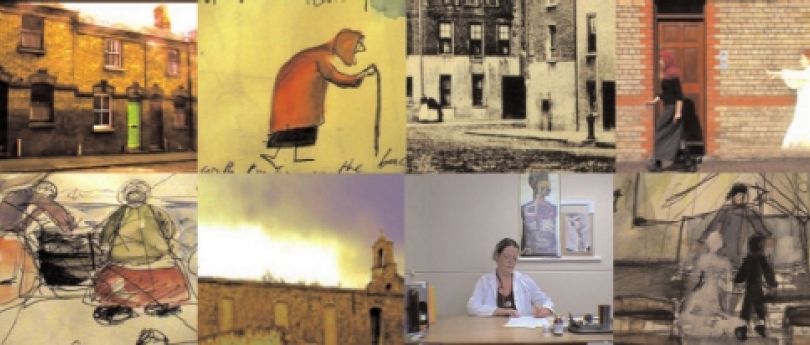

Tales of the City

Nisi’s work is powerfully visual, reflecting her training as a fine artist, and combines a documentary-like detachment with a playful range of presentation techniques, from reconstruction to animation. Her projects demand active participation on the part of the storytellers themselves (local people wherever possible), but also from the viewer-listeners. By rooting the necessarily fragmented narratives in actual spaces, she tries to achieve an immersive experience through the combination of sensory impressions from the real environment and the normally inaccessible layers of human memory presented by a range of onscreen characters.

Having completed an MSc in computer science at Dublin and a research project at Media Lab Europe, she is now studying narrative by writing a film script at Amsterdam’s Binger Institute, while consulting on mobile storytelling applications in areas from heritage to gaming. She is also working on a new project to record Amsterdam’s street songs. She talked to Jane Szita.

WHY MOBILE STORYTELLING?

We’ve got books, film, and TV — so why is it important to tell stories with mobile technologies?

Partly, just because we can, but also, stories are fundamental to every historical culture — they’re a way to understand the world and our position in it. And all technologies — from the pen to film — have generated their own language of storytelling, and their own stories. Mobile technologies too have the ability to express our stories in a unique way — and a way that also reflects the way we now move through our environment. I don’t want to sit in a cinema on a nice day, I want to go outside — so wouldn’t it be great to be able to listen to a story outside, in the sunshine? The craft of storytelling using mobile technologies is in its infancy, but there’s lots of opportunity to develop a language, a vocabulary. It’s a vital part of who we are to keep telling stories, and to find new ways of telling them. A story remains the best way to share, to communicate and to feel alive.

Stories told through mobile technologies demand user participation, yet the ‘interactive’ element of interactive storytelling always seems problematic.

You know, there have been lots of delusions about interactive narrative. It just hasn’t lived up to the hype. I think one of the main problems about it is that there’s a basic conflict between the immersive experience (the illusion) and the action needed to direct the narrative (the reality); you have to step out of the story to make a choice. I’m trying to solve that by making the physical space determine the interactive choices — so, you can go here and get one story, or go there and get another, but you remain more immersed as you walk to the different points than if you have to press a button. Interactive stories have to be carefully authored. I strongly believe in the author — even if he or she is only a moderator.

How do mobile technologies affect storytelling?

The history of narrative has been through some huge changes already. First, you had the bardic storytelling tradition, which was oral formulaic: it consisted of phrases and episodes which the storyteller could switch around with the telling. It was intrinsically flexible. Later, print fixed the narrative in just one order, while film brought new constraints. So I see interactive media as a return to the oral formulaic tradition; multiple branch structures are possible.

Having said that, do some narrative structures work more than others with the media you’ve chosen to use?

Actually, many different structures are possible with mobile technologies. You can have a modular structure — lots of self-contained stories that you can experience in any order, which is the way Weirdview works. On the other hand, you can use a linear structure, where you follow events in a chronological order; this is the most traditional option. Or you can have a navigational structure, where you actually determine the narrative order by choosing to move left or right, and so on, as we did with HopStory. You can experience the story continually, or at given points, or you can collect the instalments and view them later — either at a screening point on the site, or at home. Naturally there’s also the possibility of having different stories for tourists than for locals, native English speakers or non-native speakers, and so on.

Share

Gerelateerde thema's

Interessante ontwikkelingen die organisatiebreed worden behandeld.